Monday, December 24, 2012

THIS WEEK AT VATICAN II

DECEMBER 1962 - 50 Years Later

Pope John XXIII Named

Time 's "Man of the Year"

The opening words of the U.S. newsweekly's announcement:

The Year of Our Lord 1962 was a year of American resolve, Russian orbiting, European union and Chinese war.

In a tense yet hope-filled time, these were the events that dominated conversation and invited history's scrutiny. But history has a long eye, and it is quite possible that in her vision 1962's most fateful rendezvous took place in the world's most famous church—having lived for years in men's hearts and minds.

That event was the beginning of a revolution in Christianity, the ancient faith whose 900 million adherents make it the world's largest religion...

Thursday, December 6, 2012

THIS WEEK AT VATICAN II --

50 Years Later

December 1962

THE END OF THE FIRST SESSION

What was accomplished?

At the end of the first session on December 8, Pope John XXIII said that

“the first session was like a slow,

solemn introduction to the great work of the Council … It was necessary for

brothers, gathered from afar, to make each other’s closer acquaintance; it was

necessary for them to look at each other squarely in order to understand each other’s

hearts; and to describe their own experiences … under the most varied climates

and circumstances, so that there could be a thoughtful interchange of views on

pastoral matters.”

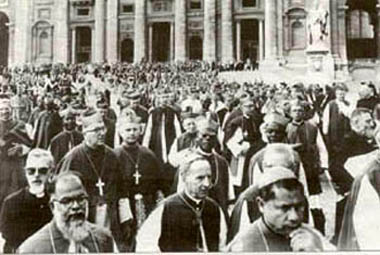

The U.S. Bishops’ own Council Daybook recalled this “human side of Council” – “Around 11 o’clock each morning, scenes

develop in the side aisles of the basilica which - except for the purple robes

and colored marbles - could be seen in the corridors and cloakrooms of the U.S.

Senate…Clusters of Bishops engage in animated conversation, form, dissolve,

reform with new members…in cloakroom and coffee lounge.”

During the first

session, the 2,500 Bishops got to know one another, realizing the vastness and

the vitality of Christ’s Church

throughout the world.

What wasn’t accomplished?

None of the conciliar documents was ready for promulgation at the end

of the first session. The Bishops decided that the schemata which had been prepared before the Council – for the most

part by curial officials – did not reflect the pastoral style of the Council.

One conciliar historian noted that: “The German theologian Father Josef Ratzinger

called the absence of any approved Council text before the end of the first

session “the great, astonishing, genuinely

positive result of the first session.” The fact that no text had

gained approval was evidence, he said, of “the

strong reaction against the spirit of the preparatory work.” This he called “the truly epoch-making character of the Council’s first session."

What were the plans for the second session?

That schedule was to be changed, because of the sheer magnitude of the work to be done – and because of Pope John’s failing health. After the first session, the Bishops returned to their dioceses “changed men”; when they returned to Rome, they would find dramatic changes, including a new Pope – who would commit himself to the ongoing work of the Second Vatican Council.

(Coming Next: June 1963 – The Death of Pope John, the

Election of Pope Paul)

- Monsignor John T.

Myler

Sunday, November 25, 2012

This Week at Vatican II

– Fifty Years LaterDecember 1962

OBSERVERS AND GUESTS AT THE COUNCIL

In the 19th

century, during the months leading up to the First Vatican Council, Blessed

Pope Pius IX wrote to all the Patriarchs of the Orthodox Church; they were

informed that, if they “ended their

separation” from the Roman Catholic Church, they would be welcomed at

Vatican I – as full, validly ordained and consecrated Bishops. During the same days in 1868, Pius IX issued

a call to Protestant leaders and their people “to return to the Catholic Church,” ending their visible separation

from Catholic unity. Both the Orthodox

and the Protestants were offended by the wording of the appeals. Neither group

participated in the First Vatican Council.

Nearly a century

later, before Vatican II convened, Blessed Pope John XXIII – with talents he had honed from years in

diplomacy --- invited Orthodox and Protestant “observers” to the Council. He joyfully welcomed them to the First

Session -- the first time a Pope had ever met collectively with a group with non-Catholic

representatives, including:

Patriarchate of Moscow

Coptic Patriarchate of Alexandria

Ethiopian Church

Armenian Catholicate of Cilicia

Russian Church in exile

(Among the Protestants:)

Anglican Union

Lutheran Federation

Presbyterian Alliance

German Evangelical Church

Disciples of Christ

‘My Brothers in

Christ.’”

In a moving response, Dr. Edmund Schlink, a

Lutheran professor from Heidelburg University, said that Pope John “by the

initiative of his heart has created a new atmosphere of openness in regard to

the non-Roman churches.”

After six weeks, the distinguished

professor Oscar Cullmann of the Universities of Basel and Paris explained to

the press that the invited Observers had received all the Council texts, attended

all General Congregations, could make their views known at weekly meetings of

the Secretariat, and had personal contact with the Bishops and their periti -- “daily reveal(ing) to us how truly we are

drawn closer together.”

However, in “The Rhine flows into the Tiber”, historian R. M. Wiltgen

recalls: “Professor Cullman also pointed

out that mistaken conclusions were being drawn from the presence of the

Observers … among both Catholics and Protestants who appeared to think that the

purpose of the Council was to bring about union between the Catholic and other

Christian churches. That was not the

immediate purpose of the Council, he said, and he feared that many such people

would be disillusioned when, after the end of the Council, they found that the

Churches remained distinct.”

Next Week: The End of the First Session

- Monsignor John T. Myler

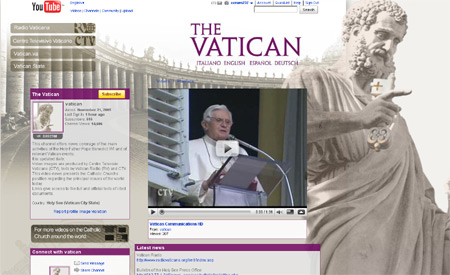

THIS WEEK AT VATICAN II

-- Fifty Years Later

November 1962

Prophetic About

Social Communications

During the first session of

Vatican II – in late November, 1962 -- the Council Fathers began discussion of

the schema on the modern means of

social communications. Over three days,

more than 50 Council Fathers made interventions about the text prepared by the

“Commission on the Apostolate of the Laity, the Press and Information Media.” Additionally, proposals on the entertainment

media had been drawn up by Archbishop Martin J. O’Connor, the rector of the

North American College in Rome, who had served since the late 1940’s as

president of the Pontifical Commission for Radio, Television and Motion

Pictures.

No previous Council had discussed

such a topic. Each Bishop received a

copy of the proposed document, which consisted of four parts:

---

The Church’s doctrine on the subject

---

The media as a help to the apostolate

---

Disciplinary norms of the Church

---

Each of the major media: the press / cinema / radio and television

In their discussion, the Bishops spoke very

favorably of the schema and the

importance of the Church’s use, cooperation with – and, in some cases –

regulation of the modern means of social communications.

Among the suggestions was the institution of an office in the

Vatican – or an expansion of Archbishop O’Connor’s commission – which would “have the task of

creating an official organization on an international, national, and diocesan

basis for the communications media and for the purpose of forming and informing

the public opinion.”

In 1962, there was no Internet…no

“emails” or “texting”…no “cable news”…no “blogs” or “instant messaging”… but

the Council Fathers saw that new ways of communicating could be – for the

Church and for the world -- a gift from God for the good of mankind.

(Next Week: Observers)

-- Monsignor John T. Myler

-- Monsignor John T. Myler

Sunday, November 18, 2012

THIS WEEK AT THE COUNCIL –

November, 1962 - 50 Years Later

REVELATION: SCRIPTURE AND TRADITION

The discussion was about God’s

revealing Himself to us: Are Scripture

and Tradition two separate, independent sources of Divine Revelation? Or are these “two sources” an inseparable

whole transmitted to God’s people generation after generation?

The U.S. Bishops’ “Council Daybook”

explained that four hundred years earlier, the Fathers at the Council of Trent

had spoken of a “unique fount” of Revelation;

in the period after Trent, the term “two

sources of Revelation” came into use among Catholic theologians during the time

when they were defending tradition against the attacks of Protestants who put

all their faith in “sola scriptura” –

the Bible alone.

Keeping in mind the ecumenical implications of the

doctrine, some of the Bishops at Vatican II wanted an answer to the question:

Are Scripture and Tradition to be considered two distinct sources – or a single

source considered in two manifestations?

At the same time, other Bishops (and some

theologians) stated that the study and development of the doctrine on

Revelation had not sufficiently matured and the time was not right for a

doctrinal decision on the matter.

Yet theologians and Council periti (experts) such as Frs. Yves Congar, Karl Raher and Edward

Schillebeeckx maintained it was clear that

Scripture and Tradition cannot be separated from one

another; rather – as God’s Revelation of Himself to the world -- they

complement one another. Congar

emphatically stated: “There is not a single dogma which the Church

holds by Scripture alone, not a single dogma which it holds by Tradition

alone.”

How could this Divine gift to the Church be stated

clearly for the modern world?

After a week of many interventions and inconclusive

votes, the Council neared the point of a doctrinal “impasse”. Would the document de fontibus revelationibus be discussed further? Or be amended

considerably? Or be rejected completely?

On November 21, Pope John XXIII intervened.

Archbishop Pericle Felici announced that the Pope had

followed the debates closely – and recognized the truth in both propositions:

that Scripture and Tradition appear as two sources of Faith, but that they

stand side-by-side as the Church’s Tradition explains Sacred Scripture. More prolonged discussions, tenacious and

unproductive, would not clarify the matter. Therefore, according to Pope John’s

wishes, a separate commission of eight Cardinals would be established to put

the teaching in a clearer, more acceptable form. In addition to the Cardinals, experts from

the Theological Commission and the Secretariat for Christian Unity would

assist.

Their task was to explicitly restate the relationship

of Scripture to Tradition – but to do so more concisely; to bring out the

teachings of Trent and Vatican I; and not so much to “defend against error” as

to speak positively and confidently.

From this “turning point”, it would take several more

sessions and over two more years to produce the Dogmatic Constitution on Divine

Revelation, “Dei Verbum.”

(Next Week: Observers at the Council)

-- Monsignor John T. Myler

Tuesday, November 6, 2012

November 11, 1962 –

Fifty Years Later

THE LANGUAGE OF THE LITURGY

The

purpose of the Sacred Liturgy is to give glory to God (sometimes referred to as

a vertical orientation). The purpose of the Liturgical Renewal would

be pastoral: so that people could better understand the Word of God and share more

fully in His sacrificial banquet (a horizontal

element). This dynamic tension was

present even prior to the Second

Vatican Council.

In

February 1962 – just eight months before the Council’s opening – Pope John had

issued an Apostolic Constitution Veterum

Sapientia maintaining that Latin should be used in the training of

seminarians. No professors or

instructors, “moved by an inordinate desire for novelty, (should) write against

the use of Latin either in the teaching of the sacred disciplines or in the

sacred rites of the liturgy.” Many

thought this signaled the end of any discussion about the using the vernacular

at Mass.

Yet, a few months later in April

1962, the Vatican Congregation for Rites issued a decree that, all over the

world, the prayers and blessings of the baptismal rite could be pronounced in

the vernacular (except for the baptismal words themselves -- “Ego te baptizo…”). This more widespread

use of the vernacular seemed particularly pastoral; parts of the rite could be used

to instruct the people gathered for Baptism.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

During October and into November, the

Council Fathers openly discussed the language of the Liturgy and the

Sacraments. Over eighty Bishops made

“interventions” about the use of Latin and the vernacular languages.

The Melchite Patriarch of Antioch – the

venerable eighty-four year old Maximos IV Saigh – spoke in French (not the

usual Latin) to the Council Fathers: “Christ Himself had spoken the language of

his contemporaries and He offered the first Eucharistic Sacrifice in a language

which could be understood by all who heard Him, namely, Aramaic.” He explained that, in the East, “every language is liturgical, since the

Psalmist says, ‘Let all peoples praise the Lord.’ Therefore man must praise

God, announce the Gospel, and offer sacrifice in every language.”

The reaction of the gathered Bishops –

from both East and West -- was very positive.

Speaking in his own name and those of several

other Council Fathers (including several Americans), Alfredo Cardinal Ottaviani

– the head of the Sacred Congregation of the Holy Office – appealed to the

Latin language’s antiquity, universality, theological precision and sign of unity. Latin – he said -- should continue to be the

language of the Liturgy, and the vernacular should be used only for

instructions and certain prayers. “Are we seeking to stir up wonder or perhaps

scandal among the people by introducing changes in so venerable a rite, that

has been approved for so many centuries…? The rite of Holy Mass should not be

treated as if it were a piece of cloth to be refashioned according to the whim

of each generation.”

Sadly, because of partial blindness, the

elderly Cardinal Ottaviani did not see the signal to finish his talk after 10

minutes nor did he hear the instruction to stop. His microphone was turned off

in mid-sentence. Some of the Bishops

applauded.

Giovanni Cardinal Montini of Milan

spoke as a mediator between opposing points of view. He maintained that changes should not be

introduced “on a whim” because the

Liturgy is of both divine and human origin; yet the rites were not completely

unalterable. “Latin should be retained,” he proposed, “in those parts of the rite that are sacramental and, in the true

sense of the word, priestly.” Without discarding the beauty and the sense of

the sacred and while retaining their symbolic power, “the rites should be reduced to a simpler, more easily understood form –

eliminating what is repetitious and over-complicated”.

The fervent discussion of the Sacred

Liturgy – the “vertical” and “horizontal” dimensions truly forming a cross -- would

continue into the Council’s

Second Session, by which time Montini would be Pope Paul VI.

Thursday, October 25, 2012

Fifty Years Later

FIVE POPES AT ONE

COUNCIL (November

1962)

Never before

in the long history of the Church’s twenty ecumenical, world-wide Councils, had

five Popes – present and future -- been gathered together in one Council aula.

They were

present in St. Peter’s Basilica during Vatican II’s first session (October to

December, 1962) : the Pope who called the Council; the Cardinal who would be

elected Pope and bring the Council to its completion; two diocesan Bishops who

would also become Popes; and a young priest-theologian who, fifty years later,

presides as Pope over a “Year of Faith” to commemorate the

Council.

Pope John XXIII (Angelo Guiseppe

Roncalli) was nearly 77 years old when elected Pope in 1958. Thought to be a mere “care-taker”, he stunned

the Church when – within the first 100 days of his papacy -- he called for a

Council. Born to poor parents in a small

village, one of 13 children, he was ordained in 1904, serving as his Bishop’s

secretary and as a chaplain in the Italian army. A scholar of Church history, he became head

of the Propagation of the Faith in Italy

and, beginning in 1925, spent nearly three decades as a diplomat of the

Holy See to Bulgaria, Turkey, Greece, and finally France. In 1953, Pope Pius XII created him Cardinal

Patriarch of Venice. He succeeded Pius

as Pope, his papacy lasting only four –

eventful -- years. Acclaimed for his

“goodness”, he was beatified -- as Blessed John XXIII -- in the year 2000.

Giovanni Battista Cardinal Montini,

Archbishop of Milan, was born in 1897, ordained in 1920, and – always in frail

health - spent almost his entire priesthood in the Roman Curia, working closely

with Pope Pius XII. While in Milan, he

was created the “first” Cardinal of John XXIII, and succeeded him in 1963 –

taking the name Pope Paul VI. Montini had been an important figure at

the Council’s first session (John XXIII kept him close, with residence in the

Papal apartments) and Papa Montini guided the Council’s last three sessions.

Sometimes described as “Hamlet-like”, he

was perhaps too quickly and unfairly berated for his 1968 encyclical letter Humanae Vitae (On Human Life). Paul died

in 1978 –after 15 years as Pope.

Bishop Albino Luciani was, in 1962, the

50-year-old Bishop of Vittorio-Venetto. Consecrated a Bishop by Pope John

himself, he had been a professor, pastor and catechist; he urged the Council to

preserve “the fundamental elements of the Faith.” At 57, he became the Patriarch

of Venice and, as Cardinal, he was elected to succeed Pope Paul on August 26,

1978, taking the names of his two predecessors as Pope John Paul I. Known as “the smiling Pope,” he held that

“the Church that comes out of

the Council is still the same as it was yesterday, but renewed. No one can ever

say ‘We have a new Church, different from what it was’”. He died on September

28, 1978 – Pope for only 33 days.

Auxiliary Bishop Karol Wojtyla

of Krakow participated in the first three sessions, returning for the fourth

as a young Archbishop. A very

active Council Father, he took part in

the debates and in the writing of the decrees Lumen Gentium (“The Dogmatic

Constitution on the Church”) and Gaudium

et Spes (“The Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World”). He

returned to his native Poland – formerly under Nazism and then under Communism -

and set about implementing the Conciliar decrees. He was created a Cardinal by Paul VI; after

the sudden death of John Paul I, Wojtyla was elected the first non-Italian Pope

in 455 years. As Pope John Paul II

he proclaimed, “Do not be afraid. Open wide the doors for Christ.”

During his 26-year pontificate, he

became a pilgrim throughout the world. He promulgated a “Catechism of the

Catholic Church”, which included the teaching of the Council. John Paul “the Great” died in 2005

and was beatified in 2011.

Father

Josef Ratzinger – 35

year old German priest and professor of dogmatic theology -- was the main peritus (expert)

to Cardinal Frings of Cologne and, like Cardinal Wojtyla, was a major influence on the writing of several of

the Council documents. A decade after

the Council, he was called away from academia to become the Cardinal Archbishop

of Munich, and then called to Rome in 1981 to head the Congregation for the

Doctrine of the Faith, working closely with John Paul II for over 20 years. At age 78, he was elected Pope, taking the

name Benedict XVI. His vision of the Council is the Church’s

“renewal

and continuity” (rather than its “discontinuity and rupture”) -- the Church

which “grows in time and develops, remaining however always the same, the one

People of God on their way.”

With that understanding of

ecclesial continuity, one might say they were “all” present at Vatican II: Pius XII… Pius XI … Benedict XV … Pius X …

Leo XIII … Pius IX … back to Trent … to Ephesus … to Peter and Paul meeting in

Jerusalem.

-- Monsignor John T. Myler

-- Monsignor John T. Myler

October 1962

Early Discussion on the Sacred Liturgy

Near the end of October, 1962, the very first general topic taken up by the Council Fathers was the Sacred Liturgy, discussing an early draft of the document which would eventually become known as Sacrosanctum Concilium.

• local languages should be used instead of Latin in the teaching parts of the Mass

• the Scriptural texts proclaimed at Mass should be more varied

• the laity of the Latin Rite should be able to receive Holy Communion under the appearance of both bread and wine

• there should be a wider provision for priests to concelebrate Masses

In historical perspective, these proposed liturgical changes were not impulsive and revolutionary – but had been preceded throughout the 20th century by both papal initiatives and liturgical scholarship. A “Liturgical Movement” which began during the 19th-century among Benedictine monks in France, slowly spread to other monasteries and countries. Some of the reforms proposed by this movement received papal support, especially from Popes St. Pius X and Pius XII. Always in fidelity to the Church, liturgical scholars attempted to share the profound meaning of various rites – especially the Mass – with the laity, leading to the publication of missals, scholarly and popular journals, a rediscovery of authentic Church music, even national “liturgical congresses.”

As late as1948, Pius XII had convened a Commission for the Reform of the Liturgy; a newly-revised Holy Week liturgy was im¬ple¬mented in 1955 – a fruit of the “liturgical movement” – of which most Catholics were unaware.

So, while there was indeed serious debate in the Council aula regarding proposed liturgical changes, these were not new, unheard of suggestions. Speaking to reporters in the Council press center, Fr. Hermann Schmidt, SJ (of the Gregorian University) and Fr. Frederick McManus (of the Catholic University of America) summarized the discussion with two deeper questions: “First, whether the texts and rites should be changed to express more clearly the divine things they signify, paving the way to full, actual, and community participation; and second, how the liturgy could be an effective influence on society, not divorced from modern civilization and the existing social situation.”

They hoped that the liturgy of the monasteries would find its way into the cathedrals and parish churches. renewal of the Divine Office and of the Psalter were also Conciliar topics, along with a discussion of liturgical needs in mission lands.

The Council discussions on the Sacred Liturgy would continue for more than a year. As one observer on Catholics in American culture later noted, “Perhaps more dramatically than any other decree issuing from the Council, the decree (on the liturgy) would touch the folks in the pews in immediate and understandable ways.”

As the Council Fathers entered a brief recess from November 1st to 4th – to observe the traditional days of All Saints and All Souls, and in observance of the 4th anniversary of John XXIII’s papacy – a “renewed” liturgy was surely in their thoughts. Fidelity, the place of Sacred Scripture, heart-felt reverence, a “ressourcement” (the study of Patristics, the teaching of the early Fathers of the Church), and the recent “Liturgical Movement” would all be factors in a reformed liturgy.

There would be renewal – yet it was surely intended to be renewal within tradition.

(Next Week: Five Popes at One Council)

Early Discussion on the Sacred Liturgy

Near the end of October, 1962, the very first general topic taken up by the Council Fathers was the Sacred Liturgy, discussing an early draft of the document which would eventually become known as Sacrosanctum Concilium.

On each Council day, always beginning at 9 AM, as many as two dozen Bishops would speak (for a maximum of 10 minutes each). During the early discussions on the Liturgy, various Bishops could be heard giving brief addresses -- called interventions, some of which were submitted as written, rather than oral texts -- requesting that:

• local languages should be used instead of Latin in the teaching parts of the Mass

• the Scriptural texts proclaimed at Mass should be more varied

• the laity of the Latin Rite should be able to receive Holy Communion under the appearance of both bread and wine

• there should be a wider provision for priests to concelebrate Masses

In historical perspective, these proposed liturgical changes were not impulsive and revolutionary – but had been preceded throughout the 20th century by both papal initiatives and liturgical scholarship. A “Liturgical Movement” which began during the 19th-century among Benedictine monks in France, slowly spread to other monasteries and countries. Some of the reforms proposed by this movement received papal support, especially from Popes St. Pius X and Pius XII. Always in fidelity to the Church, liturgical scholars attempted to share the profound meaning of various rites – especially the Mass – with the laity, leading to the publication of missals, scholarly and popular journals, a rediscovery of authentic Church music, even national “liturgical congresses.”

As late as1948, Pius XII had convened a Commission for the Reform of the Liturgy; a newly-revised Holy Week liturgy was im¬ple¬mented in 1955 – a fruit of the “liturgical movement” – of which most Catholics were unaware.

So, while there was indeed serious debate in the Council aula regarding proposed liturgical changes, these were not new, unheard of suggestions. Speaking to reporters in the Council press center, Fr. Hermann Schmidt, SJ (of the Gregorian University) and Fr. Frederick McManus (of the Catholic University of America) summarized the discussion with two deeper questions: “First, whether the texts and rites should be changed to express more clearly the divine things they signify, paving the way to full, actual, and community participation; and second, how the liturgy could be an effective influence on society, not divorced from modern civilization and the existing social situation.”

They hoped that the liturgy of the monasteries would find its way into the cathedrals and parish churches. renewal of the Divine Office and of the Psalter were also Conciliar topics, along with a discussion of liturgical needs in mission lands.

The Council discussions on the Sacred Liturgy would continue for more than a year. As one observer on Catholics in American culture later noted, “Perhaps more dramatically than any other decree issuing from the Council, the decree (on the liturgy) would touch the folks in the pews in immediate and understandable ways.”

As the Council Fathers entered a brief recess from November 1st to 4th – to observe the traditional days of All Saints and All Souls, and in observance of the 4th anniversary of John XXIII’s papacy – a “renewed” liturgy was surely in their thoughts. Fidelity, the place of Sacred Scripture, heart-felt reverence, a “ressourcement” (the study of Patristics, the teaching of the early Fathers of the Church), and the recent “Liturgical Movement” would all be factors in a reformed liturgy.

There would be renewal – yet it was surely intended to be renewal within tradition.

(Next Week: Five Popes at One Council)

Thursday, October 18, 2012

October 21, 1962 –

Fifty Years Later

Press

coverage of the first Council in nearly a century was a challenge for the hundreds

of journalists who had been assigned to Rome -- and for the Church itself.

“The first few days of the Council

sessions (mid- October of 1962) were hectic and frustrating experiences for the

press and media. The correspondents who

came to Rome were at a loss on how to report the happenings of each day. The journalists were informed that texts of

what was said by the various speakers were unavailable,” reported Bishop

Albert R. Zuroweste of Belleville, IL, chairman of the U.S. Bishops’

Communications Committee. Additionally,

some writers mistakenly expected an “ecumenical” Council to include the equal participation of non-Catholics.

Many Council Fathers from European nations

sent weekly newsletters to the their diocesan papers, but “the U.S. Bishops’ ‘Press Panel’, sponsored by the hierarchy of the

United States, was the answer to the appeal of newsmen for a competent and

reliable source of information.”

The Press Panel was set

up by the National Catholic Welfare Council (NCWC, later called the NCCB, and

today the USCCB – United States Conference of Catholic Bishops). The committee for the Press Panel was chaired

by Bishop Zuroweste who, as a priest, had been editor of his diocesan newspaper.

The press met almost daily with the

panel’s priest-experts in theology, scripture, ecumenism, canon law, liturgy

and church history – among them young Father William Keeler of Harrisburg, PA

(later Bishop there, eventually Cardinal Archbishop of Baltimore).

Newsweek and Time reporters

stated: “Nothing can substitute for interviews for more accurate reporting…What

the press needs is access to Bishops and theologians who can speak frankly

about the great event (of the Council).”

One American

Redemptorist, Fr. Francis X. Murphy - writing under the pseudonym “Xavier

Rhynne” – sent periodic reports to The

New Yorker magazine. His unofficial,

behind-the-scenes commentaries were called “frank, and sometimes irreverent”,

perhaps too simplistic in labeling “progressives” and “conservatives” -- but were

very popular.

Pope John XXIII, at an audience for 807 international

journalists, urged the press to stress the religious aspects of the

Council. Gathered in the Sistine Chapel with

the huge throng of reporters (some of whom had not been inside a Church for a

long time), the Pope asked for their “loyal cooperation in presenting this

great event in its true colors … (not) more concerned with speed than accuracy”,

nor “more interested in the ‘sensational’ than in the objective truth.”

“You will be able to see

and to report the true motives which inspire the Church’s action in the world.”

During these October

days, the attention of millions of people was focused on a Cuban missile crisis

between the US and the USSR; historical research has shown that,

diplomatically, John XXIII played no small part in averting nuclear war. The missile crisis was likely in the Pope’s

thoughts, as he urged the members of the press to work for “the interior disarmament which is the

necessary condition for the establishment of true peace on this earth.”

(Next

week: The Sacred Liturgy – First Topic)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)